- Home

- Skylar Dorset

Girl Who Read the Stars Page 8

Girl Who Read the Stars Read online

Page 8

“No, we’re not. I have to find my mothers—”

“Roger Williams, Merrow? The man who founded Rhode Island? And died in the seventeenth century? That’s who’s taking you to your mothers?”

“It’s not exactly an unusual name,” I manage.

But then the man says over his shoulder, not pausing in his strides, “But he’s right. I did found this place.”

Trow looks positively thunderous at that. “See?” he says.

“Wait.” I let go of Trow’s hand and run to catch up with the man. I hear Trow swear under his breath and catch up to me. “You can’t be that Roger Williams.”

“Why not? Did you know him?”

“No. I can’t know him. That’s the thing. He died centuries ago.”

“That is a rude thing to say to me,” replies the man haughtily, as if he really is offended, “seeing as how I am standing right here.”

“You’re dead,” Trow says flatly.

“What makes you think I’m dead?” asks the man mildly.

“The fact that you lived four hundred years ago,” answers Trow.

“If I died, where’s my body?”

“What?”

“Where’s my body? Really, you’ll do anything to excuse the evidence of your own eyes. You think everyone has to die, so you think I must have died, even though no one has ever located my body. I founded this ridiculous place, created it out of nothing but some apple trees from Avalon, and you think that no one would have bothered to keep track of my final resting place?”

“They must know,” Trow says vaguely, but I am thinking how I have never heard of where Roger Williams is buried.

“There was an old wives’ tale that I was buried in a certain corner of a certain plot of land here in Providence. They dug ‘me’ up, and do you know what they found?” He glances over at us.

Trow and I both shake our heads.

“The root of an apple tree. And then they said that was me.”

“They said what?” I say.

“They said the apple tree ate my body.”

“Do apple trees eat bodies?” I ask.

“You are finally asking the right question. But I expect nothing less. It’s the talent of those who read prophecies, to ask the right questions.”

“So you’re Roger Williams and you never died,” says Trow sarcastically. “Why didn’t you die?”

“Because I’m a good wizard, and a good wizard should be clever enough to avoid that nonsense. Here we are.” He has come to a stop in front of an old Colonial house, like any number of other old Colonial houses on the East Side.

I look at it. “This is where my mothers are?”

“Yes. It was the closest house of power I could think of to bring them. Poe used to live here, you know. He wove the power of his words into the walls. Unfortunately, they’re not exactly soothing words, but that’s how Poe was. Couldn’t get him to stop being melodramatic and fatalistic for two minutes put together.”

“Poe?” echoes Trow.

“Edgar Allan Poe,” Roger Williams clarifies impatiently. “What do they teach you in school these days?”

“They teach us science, as in living organisms die.”

Roger Williams gives him a scathing look. “You think science isn’t magic?” he says.

Which, honestly, makes the most sense of anything I’ve thought of yet.

Roger Williams turns to me, looking almost gentle. He has kind brown eyes. It’s nice when the founder of your state turns out to be a nice guy. “What has your mother told you about home?”

This gives me pause. “Home?”

“The Otherworld.”

“The other world,” I echo. “Home.” Aside from a few mentions here and there, she hasn’t really told me much about it, but that doesn’t matter, because it’s always felt like home to me, this mysterious other world she used to talk about, and now here is confirmation that it is.

From a man who should have died four hundred years ago, but really, complaining about that would be a little bit like killing the messenger.

Kind of.

“And has she told you about the Seelies?” Roger Williams continues.

“The who?”

“Oh dear.” He looks concerned now. He glances toward the house and back to me. “This is… Perhaps I should…”

“Where are they?” I demand. “Are they in there? I want to see them.”

“Merrow, you have to know that—”

I ignore him. Now that I am so close to my mothers, I need to see them, make sure they’re all right.

I march right up to the door and into the house.

My mothers are anything but all right. Mother is lying on the couch in the living room, as still as death. And Mom is sitting on the floor beside the couch, curled into a tiny ball, wailing.

CHAPTER 10

After my first stunned moment of reaction, when I just stand there staring unhelpfully, I force myself into the room. “Mom,” I say and fall to my knees next to her. “Mom,” I repeat, trying to break into the little world of her own that she is clearly lost in.

“Use her name, Merrow,” says Roger Williams behind me.

So I do, and that does make Mom look up. She stops wailing, shivering uncontrollably instead, and she stares at me, not recognizing me.

I have never imagined what it would be like to sit in front of my mom and have her look straight at me and have no idea who I am. It is horrific. No, that isn’t the right word. There is no right word for how wrong this situation is.

“Mom, it’s me,” I say carefully, tenderly. “It’s Merrow.”

The name seems to jar her at least. “Merrow,” she repeats and then reaches a hand out to feel me, as if I have changed since she last saw me. “Merrow,” she says again, and then pulls me in for a hug. “The leaves are falling,” she chatters into my ear. “The sun catches them as they fall.”

“Mom, what are you talking about? What’s wrong with Mother?”

“This world,” says Mom, and lets go of me to curl back into her ball. “Oh, this world.”

I reach out to touch Mother. I’m worried she’s going to be cold, but she is warm to my touch, and I can see now that she’s breathing. I want to reach out and shake her, wake her up, but I can also tell that it would be utterly fruitless to do it. I know it without knowing how I know it. I feel like I know so much now without knowing how, and yet it is nothing compared to how much I still don’t know.

I look at Roger Williams, and I say firmly, “You need to tell me what happened.”

• • •

Roger Williams takes us to the back of the house, where there is a small, dark kitchen.

“Tea?” he asks hopefully.

I shake my head and look at Trow. “You don’t have to stay.”

He gives me a look. “Merrow. Of course I have to stay.”

“I know, but—but—” I stop, trying to wrap my mind around what’s happening, so that I can coherently explain to Trow why I’m fine and he should go home.

“I’m staying, Merrow. Don’t be so completely absurd as to suggest that I leave you now, with everything, alone with Roger Williams.” Trow glares at Roger Williams as he says it.

So I turn to him too. And I say, “I want to know, right now, what’s wrong with my mother and my mom.”

Roger Williams looks across at me evenly. “Your mother didn’t tell you anything,” he concludes finally, heavily.

I consider. “She told me that I could see the stars dancing, that I could read things in tarot cards, dust motes, cinnamon and sugar, and salt and pepper, coughs and sneezes.”

He smiles faintly across at me. “And can you?”

“Yes. No. I mean, I don’t know.” I pause in frustration, wondering how to find the right words. “Sometimes I feel li

ke I understand what she’s saying to me, but then again, sometimes I feel like I have no idea what she means. I mean, I never know what they’re saying to me. It’s just feelings. When it’s anything at all.”

“I daresay you will know now,” says Roger Williams with finality. “As much as anyone ever knows.”

I don’t contradict him, because I don’t actually care about the stupid stars at the moment. “How do I fix Mom and Mother?”

“My dear, we must start at the beginning,” he says. “First things first: you are a faerie.”

I blink. Great, I think. This guy really is insane. I guess him saying he was Roger Williams should have been my first clue… “I’m a what?”

“A faerie.”

I look behind me, suddenly thinking maybe I’ve sprouted wings. I haven’t (which is, frankly, a little bit disappointing).

Trow says, “This is ridiculous—”

“If you are going to belittle the truth after requesting it,” cuts in Roger Williams icily, “you are welcome to leave.”

Trow falls silent, but he doesn’t look pleased about it.

“A faerie,” I say flatly. “You think I’m a faerie.”

“I know you are one.”

“A faerie. What do you even mean by that?”

“You’re not from the Thisworld. You’re from the Otherworld. Where such things exist. Faeries and ogres and gnomes.”

The Otherworld. I think of my mom’s yoga studio. I think of her constant references to the other world, the world not our own, but the world where we were more at home, the world where we really belonged. All this time, I thought it was metaphorical. But now, out of nowhere, a man claiming to be Roger Williams is using the same exact term in the same exact way. The Otherworld. As if it’s a real place.

“Faeries and ogres and gnomes and people who found states,” drawls Trow sarcastically. He clearly doesn’t believe anything Roger is saying, but my head is whirling around that single phrase. The Otherworld.

“I am a wizard,” Roger informs him primly. “But I am not from the Otherworld. We wizards bridge both worlds. So do most other creatures these days, but in the beginning there were us and the Threaders, but the Threaders were the elite. Not just the workaday wizard, trying to get into a golden Otherworld. Those were good days…”

He is looking into the distance, and I can tell he is remembering a time and a place far away from ours.

And I don’t have time for that. I have much more pressing, here-and-now problems. “But what does this have to do with my mothers?”

“Well, your mother is a faerie too, of course. I mean, your real mother. Not the one laying down in there.”

“Mom, not Mother,” I clarify. Of my two mothers, it’s got to be Mom who’s the faerie.

“Merrow, you don’t really believe this is true?” Trow cuts in.

I look at him. “Mom talks about the Otherworld. She…I don’t know, do you have another explanation?”

“Yeah, I—” I watch as Trow’s eyes run through all of the other possible explanations and come up empty. He looks at Roger, then back at me. “But, Merrow—”

“Tell me what I have to do for my mothers,” I demand of Roger.

“Neither one of those beings in the other room is your mother. Your mother is a Seelie faerie.”

I stare at him. “A…what?”

“A royal faerie.”

“My mother is a royal faerie?” I echo.

He nods.

“My mom’s not my mother?” My voice is so faint I can barely hear it.

He shakes his head.

I swallow, trying to keep my thoughts organized. “Then…how did I end up with Mom?”

“Ah, that’s where things get complicated.”

“That’s where things get complicated?” I exclaim.

“There was a prophecy. Four faeries of Seelie blood, born of the turning of the seasons, would destroy the tyrannical reign of the Seelie Court and bring longed-for peace back to the Otherworld. And you are one of them.”

“I’m ‘one of them’?” My feeling that things were going to start making sense went out the window long ago, but this particular assertion by Roger is taking the cake for me. “I’m a…special faerie…who’s going to…bring peace?” Because I’m clearly not. I’m Merrow Rodriguez-Chance, and I have two mothers, and they need my help. I don’t care about this Seelie Court thing.

“Along with three other faeries, yes.”

“Three other faeries. I don’t know three other faeries.”

He gives me a knowing look. “Don’t you?”

I want to scream in frustration. What the stars is he talking about? “What does this have to do with my mothers?”

“That is what happened to your mothers—the Seelie Court, finding where you were hidden and coming after you.”

I think of the destroyed house. “So they fought. My mothers fought.”

“Of course they fought. They fought for you. They fought to delay the prophecy. As if the future can be pushed back. As if time can be stopped. None of us—not even me—have ever accomplished that. Time, at whatever pace it decides to move, always keeps moving forward. There’s no choice. We may pick and choose which constellations to read, but we cannot stop the fact that they do dance. So the prophecy has begun.”

“How? Why? Why now?” I ask desperately. I had this somewhat, kind of normal-ish life, and I don’t understand why I don’t have it anymore.

“Did you tell someone your birth date?” Roger Williams asks me knowingly.

And what does that have to do with anything? “What?”

“You did,” Trow contributes quietly. “You told me: the summer solstice.”

So? I don’t understand why that’s important. “Only because today’s not my birthday.” I look at Roger Williams, quizzical and confused. “I only said it because today is not my birthday. ‘Happy birthday’ was written on the wall at home, and I don’t know why.”

“Because it reveals you. It makes you more easily locatable to them, uncovers you. You say your birth date, and you come into who you are, who you’ve always been.”

“That doesn’t—” I start automatically, but then I pause. Because…because maybe it does. Maybe it does make sense. Not the why of it—that is never going to make sense, but Mom has always said that why questions are overrated, that it’s her least favorite word—but the fact that I said my birth date and suddenly, for the first time ever, I had the kind of flash of certainty I’d always wanted from the stars and the cards and the salt. Not the vague sort of feelings I’d get before, but the clear vision of Roger Williams on the front walk, the knowing sureness that there was a future path I could take to get to him.

Roger Williams looks as if he knows exactly what I’m thinking. And he’s a wizard, I guess, so he probably does.

I steel myself, pushing every why question down. The whys don’t matter right now. I don’t have time to worry about the unbelievability of this whole story. There is only one thing I have time to worry about.

“How do I help my mothers?” I ask firmly, calmly, evenly. “What do I have to do?”

“You can only help your mothers through fulfilling the prophecy, and you need the three other faeries to do that.”

“I don’t know three other faeries!” I protest desperately. “I basically only know Trow!”

“You can read prophecies. A very tricky thing to do, you know. The future isn’t written down yet, so it exists in endless possibilities. It is a special talent, for the stars to talk to you, for you to see the routes of probability and find your way over them—one I have always envied.”

“So you think I’m going to look at the stars and know who these three other faeries are? Why can’t they just look at the stars and know who I am?”

“We are assuming they have differe

nt talents. We were waiting for the time when your talent would wake up.”

“I don’t understand what this has to do with Mom and Mother. How is this going to help them? I need to help them. I don’t care about the prophecy right now.”

“You should always care about the prophecy,” Roger Williams tells me. “The prophecy is you.”

“That is definitely not true,” I say simply. “I am much more than this thing I’ve never even heard about until now.”

Roger Williams sighs at me. “When you were born, the woman you call your mom found you. She can also read prophecies, so she knew precisely what you were. In those days, the connections between the worlds had broken down. It was not easy to go back and forth, but your guardian knew you would not be safe in the Otherworld. She fought her way through with you, to here, and I agreed to harbor you until such time as the prophecy might come true. Which appears to be now. Which is how this situation happened. If your guardian had but come to me to tell me that the wheels of the prophecy had begun to turn… But no, instead she chose to try to hide you. From the stars themselves! As if such hubris has ever been successful. As if anyone has ever successfully stood strong when the stars began to choose their whirling paths. Your destiny was foretold, and your guardian knew this.”

I think of her locking me in my room that day. Somehow. Trying to keep me safe. A faerie who smuggled me out of the world where I was born, my home world, the Otherworld, and brought me to this one. “Is Mother a faerie too?”

“You mean the other one? No, she is a human.”

“Does she know we’re faeries?”

Roger Williams looks a little offended that I’m asking him this question. “I have no idea.”

“So the Seelies came in search of me and what? What did they do exactly? How do I reverse it?”

“Our defenses here have never been as good as I might wish. Once the Seelies realized you were here, once the stars had begun to turn that way, they came for you immediately and succeeded in getting through. I am holding them away from you now, but only just barely. They are getting much closer to you than I would like. Which is why you must quickly determine where the other faeries of the seasons are and get to them.”

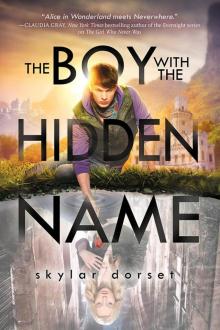

The Boy with the Hidden Name

The Boy with the Hidden Name The Girl Who Never Was

The Girl Who Never Was Girl Who Never Was

Girl Who Never Was Girl Who Read the Stars

Girl Who Read the Stars The Boy with the Hidden Name: Otherworld Book Two

The Boy with the Hidden Name: Otherworld Book Two