- Home

- Skylar Dorset

Girl Who Read the Stars Page 7

Girl Who Read the Stars Read online

Page 7

I push back at the anger and do some three-part breaths, because I need to keep it together, damn it. Trow, I think. Maybe I can find Trow, and maybe he’ll know what to do. Even if he doesn’t know what to do, I am suddenly desperate to see someone who is part of the life that I had. I need to find Trow, and I need to have him be normal, unlike everyone else that I love right now.

I look at my watch and figure out what class Trow would be in. One of the first-floor classrooms, luckily, and I creep up to the windows, staying ducked underneath them. I’m going to have to become visible in order to see into the room. And hopefully Trow will be there. What if it’s one of those days when Trow isn’t there? What am I going to do then?

I refuse to let myself contemplate that. Trow is going to be there and it’s going to be normal, I tell myself. Shanti, shanti, shanti. And then I take a deep breath and peek up over into the window.

Trow is sitting right there, and he happens to be looking right at me, and I could cry at my suddenly excellent luck. I so need that after the rest of today.

Trow blinks at me, surprised to see me, and tilts his head in confusion, lifting an eloquent eyebrow at me.

I manage not to burst into tears, and I beckon him and then duck back underneath the windows and move over toward the front entrance of the school, keeping to the hedges.

It feels like it takes forever for Trow to emerge, but maybe it’s just a couple of minutes. I’ve lost all sense of time. I feel like this day has been my entire lifetime.

When he finally walks outside, I lose my meager grasp on my composure. I fly to him and he catches me up, and then I am sobbing into the lapel of his coat and clutching at him desperately.

“Okay,” he says to me soothingly. “Shh, shh, shh. What’s wrong?”

I try to tell him, but I’m practically hyperventilating with sobs.

“Merrow,” he says gently and nudges me away from him just as gently. “Three-part breath, Merrow, right? Let’s try one.”

He walks me through one and then another, and I look up at him and he is smiling so sweetly. He lifts his hands up and wipes at the tears on my cheeks with his thumbs. Which just makes me start crying again. Trow is better than just normal; Trow is lovely. Not that he isn’t normally lovely—he’s just extra super lovely right now.

“Okay, Merrow, tell me what’s wrong.”

I lick my lips and I swallow and I don’t even try a three-part breath because I’m never going to get it in. I just blurt out, “I think my mom’s gone insane.”

Trow doesn’t even look surprised. “What do you mean?”

“She went crazy over…over you,” I admit. I hadn’t thought through having to break that part to him. “And I don’t mean just, you know, normal overprotective mom stuff that might make sense if I had an overprotective mom. She wouldn’t let me go to school today because I’d see you here. As if I was just never going to go to school again. She’s completely irrational about you.”

Trow doesn’t seem to know what to make of this. “Would it help if she met me?”

He’s not understanding. He’s thinking this is just disapproving mom stuff. “No, Trow, it’s super beyond that now. She locked me in my room.”

“To keep you from going to school?” Trow sounds incredulous. “Does she do that a lot?”

“Trow.” I take a deep breath. “My bedroom door doesn’t have a lock.”

He stares at me. “Then, Merrow, how could she—”

“It gets worse.”

“It gets worse than you telling me that you’ve spent all morning locked in a room that doesn’t have a lock?”

“I climbed my tree to get out, and I went to find my mother because I thought maybe she could talk some sense into my mom, and my mother never went to work today. Trow, what if my mom has her locked in the house too? What if my mom has completely snapped? What am I going to do if—I mean, she’s my mom and I need her to—I can’t—”

“Merrow, take a deep breath. Just one, even. Doesn’t need to be three-part. You’re not breathing.”

“For obvious reasons,” I shout at him, struggling to follow his directions.

“I’m not arguing with you there,” he says grimly, reaching out and rubbing his hands along my upper arms and shoulders. It warms me up and feels soothing and comforting. “We should call the police.”

“And say what? She hasn’t committed a crime. She just…” I refuse to harbor the possibility that my mom has done anything more severe than locked us into rooms. I just… “Trow, we can’t. Please. Please can you just come with me and we’ll just…see? Before we get the police involved? Please, Trow, I…” I trail off, realizing I’m not breathing again, and I focus on that.

Trow’s gaze on me is pitying, and I hate to see that. He thinks I’ve lost it too. He thinks I’m being delusional. I look away from him, at the school, marveling that we’ve been just standing right outside it having this intense conversation. After a second, Trow says, “Okay. Let’s go.”

• • •

Trow holds my hand the whole walk back to my house, and I am grateful for the contact. He doesn’t talk to me, which I am also grateful for. I can’t handle talking right now. I keep trying to do three-part breaths, but I can’t clear my mind. It is a cacophony of panic.

My house looks utterly, perfectly normal from the outside. And both Mom’s and Mother’s cars are parked on the street in front of it. I didn’t notice when I fled earlier. I stand with my hand curled into Trow’s and look from their cars to our house, quiet and cheerful. Except for the fact that our curtains are drawn. We never draw the curtains during the day—Mom likes the brightness in the house.

I swallow and, as if we are perfectly attuned, we both begin walking up the walk together. When we reach the two shallow steps that lead to the front door, we also both pause at the same time. There’s a…buzzing feeling, like static electricity, and underneath it, a sound almost like bone-deep sorrowful wailing, and then, farther underneath that, bells, like I heard in Mother’s office.

I really am going completely insane. It’s terrifying.

Except that Trow says, his voice low, “What is that?”

“You feel it too?” I say, relieved beyond words.

“And hear it. Where are the bells coming from? And is someone crying?” It’s Trow who steps forward, going to open the door to my house.

At the same moment that I realize I don’t have a key, the door swings open under Trow’s hand. Maybe that shouldn’t be unsettling, given that both of my mothers appear to be home, but I shudder nonetheless.

I join him in the doorway and peek my head past him.

“Merrow,” he begins, turning as if to shield me, but I push him away and step into the living room.

The living room is a mess. A disaster area. All of the furniture has been turned upside down, all of the books and photos and knickknacks scattered about. The pictures on the walls have been pulled off and smashed. My shoes crunch on the pieces of them as I walk farther into the room. The room is such a disaster that even the ceiling has been attacked, plaster dust raining down on me as I stand there, drinking it all in. There is even wallpaper peeling from the walls around me. What the stars happened in here?

And on one of the walls, the one over the couch where a watercolor of a pretty, fuzzy landscape had once been, painted in glowing silver are the words HAPPY BIRTHDAY.

“Is it your birthday?” Trow asks me, confused. “Or one of your moms?”

“No, my birthday is June 21,” I say dazedly, staring at the message.

“The summer solstice,” says Trow.

“What?” I blink away from the message.

“The summer solstice.”

Why is he talking to me about this? I turn away from him and shout for my mothers, getting no answer. I don’t understand what this is. I don’t understand what could h

ave happened. I walk swiftly through the rest of the rooms on the ground floor, all of which are a mess, all of which are empty and silent. The static buzzing and the wailing bells no longer haunt me here in the house. Or maybe I’m just too busy freaking out over everything else that’s going on right now.

I take the stairs two at a time, still shouting for my mothers. I go right past my room, into their bedroom. It too has been destroyed, and scattered all over it like snowflakes are my mom’s tarot cards. I find myself on my hands and knees, pulling them all together, shuffling them, dealing them.

“Merrow,” Trow says to me carefully, as if he doesn’t want to disturb me but feels like he has to.

I shake my head, dealing the cards again. “But it doesn’t mean anything! I keep dealing the cards, but I don’t understand the reading! Were they telling me this and I didn’t understand it?” Annoyed, I fling the cards away from me. They spiral out, fluttering down to the carpet, and I sit there, exhausted and frustrated. “Where can they be?”

“We should call the police now.”

“And say what?”

“That your mothers are missing. That it looks like they were kidnapped.”

“I don’t understand. When did this happen? How could I not have heard it?”

“Maybe it happened after you left,” suggests Trow.

So all morning I sat locked in my unlockable room, my mothers deaf to my entreaties. I climbed out the window to the tree, and then after I fled, someone came and kidnapped them. Who? How?

“But how did this whole mess happen?” I ask, bewildered.

“They put up a fight?” guesses Trow.

“A fight? This is not just a fight—this is a war. Trow, the ceiling is coming down.” I gesture above us, where dusty plaster is raining down on us from gouges in the ceiling.

“What do you want to do?”

“I don’t know,” I say. “I just don’t feel like we should call the police.” Everything around me is fuzzy and out of focus, but that particular detail seems clear—whatever is going on here, the police can’t help. I don’t know how I know that—I just know. Better than I’ve ever known anything from the stars or cards or spices or dust.

I stand up wearily and walk down the hallway and pause at my door. I reach out to open it, but the doorknob jiggles uselessly, just the way it did when I was on the other side of it. “Still locked,” I say glumly.

“Merrow, we’ve got to tell—”

“Shh.” I launch forward suddenly, clapping my hand over his mouth. He looks at me in alarm. “There’s someone in the house,” I hiss.

He lifts his eyebrows and moves my hand away from his mouth. “You heard something?” he asks, his voice barely a whisper.

“No,” I whisper back, licking my lips. “I just know that someone’s in the house. Or…outside of the house.”

“What?” Trow sounds even more confused.

But I can’t explain it. I feel like it came to me in a flash: a man, older, in corduroy pants and a button-down shirt, standing on my front walk. As vivid as a memory. And maybe it is a memory. Is it a memory? I’ve never had anything like this happen to me before, and I don’t know why it’s happening now, and I’m not even sure what it is, but I feel like there’s someone here. I feel like I know this as well as I know my name. I feel like it is the only thing that I know.

I push past Trow and almost fall down the stairs in my haste to get to the front door.

Then I pull the door open, and there he is, just as I remembered him. Or…predicted him? I think of the future Mom was always telling me to try to see, the stars dancing overhead, the tarot cards, the salt and pepper and sneezing. All of that nonsense, and suddenly for the first time, I feel like I understand it. This flash of intuition makes sense to me the way nothing else has in my life: there is a man outside my house, in the past or the present or the future—it doesn’t matter. I almost don’t understand why Trow doesn’t see how much it doesn’t matter.

“Hello, Merrow,” says the man, and smiles at me.

I stare at him. I can feel Trow behind me, the heat from his body protective and reassuring.

“Do you know this man?” he asks, pitching his voice low so that only I can hear him.

I’ve never seen him before in my life. But it doesn’t matter. Because I’ve seen him before in my future.

I step forward, toward him. “Who are you?” I ask, trying to sound assured and confident.

“Asking for names already. You’re quite prepared to get down to business, aren’t you?”

None of that was his name. “Who are you?” I ask again, and I actually no longer feel uncertain. The confidence in me is innate and strong. This has happened before, and it will happen again. All of the threads of time, running concurrently, have suddenly converged, and I feel like I can touch all of them.

“It’s a long story. Won’t you come with me?”

I’m ready to follow him. In fact, I walk down the first step and Trow pulls me back.

“Why?” Trow asks.

“Aren’t you looking for the—” The man pauses. “People who live here?”

My mothers. I turn to Trow, frantic. “He knows where my mothers are.”

“Yes,” Trow agrees, frowning at me. “And don’t you think that’s suspicious?”

“It is what is. Or what was supposed. Or what was thought. That’s the dance the stars have chosen. Finally.”

“Merrow, you’re not making sense.” Trow’s frown flickers into concern. He actually lays a hand on my forehead as if I’m running a fever.

“Yes, I am,” I insist. “I’m making sense the way I’ve never made sense before. Everything is making sense. Finally. Can’t you feel it?” I take his hand in mine, wishing I could help him see the way all of the dances of the stars are overlapping each other in my mind’s eye, and I know exactly which constellation of them to flit over.

“Merrow, your mothers are missing, your house has been destroyed, and a man you’ve never seen before has just shown up claiming to know where they are. And you want to go with him.”

“I know,” I agree. “It makes no sense.”

“Right,” says Trow, relieved. “That’s what I’m trying to—”

“And that’s why it finally makes sense. Finally. All of it. Finally.” I am oddly, contradictorily happy. I feel like I can take a nice, deep breath for the first time in my life. This insane day has clicked into sense, and I can’t explain it beyond that, just that it feels right. Once I had the flu and skipped yoga for several weeks, recovering. After the first class I took upon my return, I realized that I could turn my neck over my shoulder so much farther than I had been able to before the class—but I had never noticed until that moment that my neck had been tense. I feel a little like that now, like I have come home to the way I am supposed to be and I never realized before exactly how ill-fitting this world had been.

I turn to the man on the walk, ignoring Trow’s continued sputter of protest, because there’s only one thing missing here. “Where are my mothers?”

The man smiles at me, and I trust him implicitly, because we have done this before, he and I, in one of the dances of the stars; I had just forgotten. “This way,” he says and begins walking, and I follow him.

Trow, reluctance in every movement, falls into step beside me.

CHAPTER 9

The man talks as we walk through the winding streets of the East Side. The early winter twilight is falling, darkness stealing its way up the hill and through the alleyways, filling in the gaps of the trees’ empty branches. I sense the bright glow of the stars over my head, but I don’t look up. I am focused on going to my mothers.

“I did the best I could,” the man says.

I had not been cold, basking in the warmth of the stars overhead and the world clicking into sense and my mothers coming closer to me,

but everything retracts somewhat, retreats at his words, and the cold of the air around me seeps through. “What do you mean?”

“It was too late by the time I got here. Your mother sent the word too late. Stubborn and in denial—you who read the prophecies, you are the best at denial. But I suppose maybe you have to be, or the weight of the possibilities—of the futures that could be—would keep you from ever locating the here and now.”

Objectively, I feel like nothing he is saying should make sense. And it doesn’t really. And yet like everything else since I wandered through my devastated house, it makes the most perfect kind of sense.

“By the time I got to them, the Seelies had done… Well, you’ll see.”

I don’t like the cryptic foreboding of this.

“Who are the Seelies?” Trow asks. “Are they a gang?”

The man spares him a brief look. “Where did you get the hanger-on?”

I bristle on Trow’s behalf. “This is Trow.”

“You shouldn’t tell me his name, my dear. It is both the most important thing about him and the least important, since I don’t care. We have this well in hand, Trow. You can go now.”

Trow flinches at the dismissal and says, “I’m not leaving her with you. I have no idea who you are. Neither does she. I have no idea what is going on. Neither does she. I think we should call the police.”

“What would the police do with an Otherworld uprising? They lack jurisdiction.”

“You’re not making sense,” Trow says between gritted teeth.

“Trow, it’s all right,” I tell him, taking his hand to try to comfort him.

“No, it’s not. Who are you?” Trow demands of the man.

The man pauses, drawing himself up to his full height and looking at Trow down his nose, even though, at his full height, Trow probably has at least an inch on him. “Roger Williams,” he answers.

“Oh, come on,” says Trow.

The man shrugs and resumes walking.

Trow uses his hand in mine to pull me in the opposite direction. “Come on,” he says. “We’re going.”

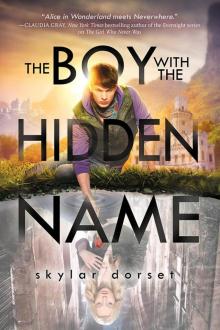

The Boy with the Hidden Name

The Boy with the Hidden Name The Girl Who Never Was

The Girl Who Never Was Girl Who Never Was

Girl Who Never Was Girl Who Read the Stars

Girl Who Read the Stars The Boy with the Hidden Name: Otherworld Book Two

The Boy with the Hidden Name: Otherworld Book Two