- Home

- Skylar Dorset

Girl Who Never Was Page 5

Girl Who Never Was Read online

Page 5

Ben laughs, and then he says, “You are delightful,” and his voice is warm, and so I am warm. I am sure I have blushed bright pink with pleasure, and I wish it were dark so Ben wouldn’t be able to see me.

“Why?” I ask.

“Because. All the many questions you could have asked me next, and what you ask me is about the disappearance of Boston’s rats.”

“If the rats were part of the enchantment, I could have done without them.”

“Don’t blame me for the rats; that’s Will. He’s obsessed with all creatures like that, rodents and reptiles and such.”

“You mean Will from the Salem Which Museum?”

“I mean Will from the Salem Which Museum.”

“He had an iguana.”

“Not surprising,” says Ben.

“So he’s involved in this too?”

“It was all his idea.”

“He was the one who gave me the books, the books with my aunts in them.” I pause. In a world where Ben is talking seriously about enchantments, this seems like a perfectly normal question. “Are my aunts immortal?”

Ben hesitates. I look at his profile—since he’s looking at the tracks, not at me—but his expression is unreadable. Eventually he responds, “You should wait and ask them that question. It won’t be much longer.”

Which means the answer has to be yes. I ponder that, trying to make that sound like something that could be true.

I decide to change the subject.

“So. The T connects…what did you say?”

“The Thisworld—the world where mostly humans live—and the Otherworld—the world where mostly nonhumans live—two worlds, existing side by side, but only overlapping in certain places.”

“And Boston is one of them?” This seems difficult to believe. Boston has never seemed especially magical to me, but maybe that’s because I’ve been enchanted to think otherwise.

“Boston is one of them,” confirms Ben. “Park Street station happens to be one of the busiest portals in the Otherworld. Haven’t you ever noticed how people pop up here out of nowhere?”

I have, but I’ve always just dismissed that. More of my enchantment, I guess. “What’s a portal?” I ask.

“A safe place to go when an enchantment is dissolving and a way to get from one enchantment to another—and one world to another. It would have been much easier for us to get back to Boston, though, if you hadn’t named me a few times and then rained on me for good measure.”

“Why?” I ask.

“Because then I could have just jumped us,” Ben says. “I’m a traveler. We don’t wait for trains.” He says the word with disgust, like it’s beneath him. Then he adds, “Normally. When I haven’t been rained on and named. Not that I’m blaming you or anything.” He winks at me.

“A traveler?” I say.

“Best traveler in the Otherworld,” he proclaims proudly, then frowns. “Possibly only traveler in the Otherworld.”

“Only?” I say, but suddenly there is a squealing of track up above us.

Ben jumps a mile.

“It’s only a Green Line train coming,” I tell him, because he looks terrified.

“Exactly,” he says and abruptly leaps onto the Red Line tracks.

I blink in shock. “What are you doing?”

“Can’t wait anymore. Come on.”

“Come where?”

“With me.”

“On the tracks?”

“Yes.” Ben sounds exasperated. And also frightened. And the last time Ben sounded frightened, all of Boston winked out of existence around us, so I jump onto the tracks with Ben.

Now that I am on the tracks with him though, Ben hesitates.

“Ben?” I query.

“Nothing for it,” he says. “Green Line train. We have to go.” And he starts walking, looking grim.

“Why? What’s a Green Line train?”

“Nothing good. Worse than the goblins, so this is the lesser of two evils.”

“But we were just waiting for a train. Why wasn’t the Red Line train bad?”

“Because only the Green Line is evil,” Ben explains impatiently.

I catch up to what else he said. “Wait, goblins?”

“Yes. Watch out for them. Their talent is seduction, so be on the lookout.”

All of this is making even less sense than everything else. “What?”

“Just think, you know, how you don’t want to be seduced, and you’ll be okay.”

“What are you talking about?” I complain.

We had been walking at a brisk pace, but Ben stops suddenly. “Do you hear something?”

I do hear it. I look behind us. “A train.”

“They jumped the tracks,” breathes Ben, sounding terrified, and abruptly takes my hand again. He speaks directly in my ear, over the noise of the oncoming train. “Whatever happens, do not let go of my hand, do you hear me?”

He doesn’t wait for me to reply, just takes off at a mad dash. He is running impossibly fast, and I am stumbling in his wake, but his hand stays in mine, and he keeps pulling me up. He does not ever look behind, at me or the train, but I keep looking behind obsessively, and the train is barreling down on us. I have no idea what Ben’s plan is, but I am hoping he has one, and then, suddenly, the train disappears and the tracks disappear and it is blinding sunlight, and Ben tumbles to the ground of a grassy meadow, and I tumble right over him and, in my shock, let go of his hand, tumbling head over feet down a steep hill until I land with an unpleasant and painful splash in some kind of rocky brook.

I sit there for a second stupidly, winded and getting soaking wet, until I become aware that there is a rat looking at me across the brook.

And Ben said there wouldn’t be rats, I think, which is the first thought I feel like I can think.

And then the rat says, in brusque, clipped, perfect English with not a hint of a ratly squeak, “My stars, what the hell are you doing here?”

CHAPTER 5

I do not answer the rat. It never occurs to me to question that the rat can talk—given the day I’ve had, that seems like the most normal thing to have happened in hours—but it does occur to me that I no longer understand the rules of my life, this life where saying a single name can cause all of Boston to wink out of existence around me. So I consider it wiser not to answer the rat, and anyway, I don’t know what the hell I’m doing there, so I can’t answer the question. Maybe the rat is a goblin like Ben warned me about? This seems preposterous, but no more preposterous than anything else, so I think, very firmly, I do not want to be seduced. Which I don’t.

I scramble my way out of the brook, tumbling inelegantly into a patch of cheerful pink tulips. And then I take a second to catch my breath and try to get my bearings in this new world. First things first: Where is Ben?

I glance back at the hill I tumbled down, which is extremely steep, and think—hope—that Ben must be at the top of it. I pick myself up, dripping wet, and go to start climbing up the hill, and that is when the tulip grabs me.

It probably shouldn’t be surprising, because I should probably stop being surprised by anything at this point, but I let out a little cry as the tulips entwine themselves around me and pull me back down into them. I struggle, pulling tendrils of leaves off of me, and think that I never before really thought of tulips as being deadly, but their soft petals brushing against me are terrifying. I kick and flail and then think suddenly, slicing through my panic, I do not want them to touch me.

The tulips shrink back, and I scrabble away from them, breathing hard. I stare at them in disbelief, because they are back to looking like a typical clump of tulips, innocent and not at all murderous.

“What the hell,” I say out loud, because I can’t help it.

“Well,” huffs the rat. “What did you expect? You trampled

them on your way out of the brook. They had to defend themselves somehow.”

I ignore him and start struggling my way up the hill. By the time I get to the top of it, I am exhausted and hot from the sun. I would love to take off my sweatshirt, but Ben had said it was an enchantment, and I’ve had enough of breaking enchantments for the time being.

Ben is sprawled spread eagle on his back in the middle of the meadow. The rat had leapt easily up the hill in front of me, and it is now sitting on Ben’s chest, its nose up against his. It looks up at me as I finally reach them, its beady black eyes accusing.

“You’ve killed him,” it says.

You know how people always say things like “my heart stopped”? It actually happens to me then, in that moment. “What?” I gasp and fall to my knees next to Ben and shake him. He is still and lifeless and does not react at all. “How…?”

“Hmph,” says the rat, sounding disgusted, and jumps off Ben’s chest.

I barely notice, because I am busy thinking, Whatever happens, do not let go of my hand. I look at my hand, and I look at Ben’s, and I fit them together.

His eyes flutter open and squint into the sunshine above him. “Oh, good,” he says drowsily and closes his eyes again. “We made it.”

I barely have time to be relieved about this, never mind time to be curious about this, when Ben suddenly snaps his eyes open and sits straight up.

“We made it,” he repeats, looking at me. “Very good.” He startles me by releasing my hand and suddenly putting one of his hands on either side of my head and then, astonishingly, kissing my forehead exuberantly. “Very good,” he says again and picks himself up lightly. “Let’s go.”

“Ben,” I protest. I want to stop running around for a few minutes so he can answer my questions. I want to point out that he was apparently just dead and I revived him by holding his hand.

“Oh,” Ben says flatly, and I realize he is talking to the rat. “You’re here.”

“Of course,” snaps the rat. “Where else would I be? And you brought her here?” says the rat. “Your mother was right: you are the wrongest creature in the Otherworld.”

“I didn’t have a choice,” he tells the rat and then takes my hand and uses it to pull me up. “Come on, we have to go.”

“Where are we?” I ask, because this is clearly not anywhere near Boston, where it had been damp, chilly nighttime, not sunny, hot daytime.

“Why didn’t you have a choice?” asks the rat. It is now trotting along behind us as we walk through the meadow.

Ben answers the rat instead of me. “There was a Green Line train.”

The rat gasps. I have never heard a rat gasp before. It is quite something. “A Green Line train,” it says. “Benedict…”

“I know,” Ben replies grimly.

“Wait. What do you know?” I ask. “Why is a Green Line train so bad?” By now, I am ready to scream with how little sense any of this makes.

“So you brought her here?” shrieks the rat.

“I was wet,” grumbles Ben. “And she named me. A lot. This was the best I could manage. But it’s fine. It’s only a brief stop. We’ll be on our way to Parsymeon in no time.”

“She named you? How does she even know your name? How could you be so clumsy?” shouts the rat.

“I’m sorry,” I say sweetly. “My father told me his name; it wasn’t Ben’s fault. And I don’t mean to be rude, but who are you?”

The rat makes a noise I can only describe as, well, a squeal. “The impertinence!” it exclaims. It is making such a huge deal, hopping around the grass in some sort of stricken dance, you’d think I was trying to kill it.

“Never ask for names,” Ben tells me. “Too much power in a name, no one will give their name to you, and if you ask for it, they’ll react like…well, like that.” Ben nods his head vaguely toward the rat. “Anyway, he’s my father.”

This takes the cake for most ridiculous thing I’ve heard so far today. “Your father?” I echo.

“Sadly,” sighs the rat.

“So.” I study Ben, trying to find rodent features in a face that I have always personally considered quite handsome. “You’re a…rat?” I venture.

Ben looks indignant. “Don’t be silly,” he says impatiently. “Do I look like a rat?”

“No. But then, what are you?”

“A faerie, of course,” he answers. He is saying all this as if he would have expected me to know these answers already. Ben and I need to have a chat about things that are obvious and things that are not.

“But your father’s a rat?”

“Why do you keep saying I’m a rat?” snaps the rat.

I stare at him, and we all stop walking.

“Because you look like a rat,” Ben snaps back.

“I choose to personify as a rat,” says the rat primly. “But I am clearly a faerie.”

“And he thinks I’m the wrong one,” mutters Ben.

I consider my next question because, after all, I can only ask one at a time. Ben says he is a faerie. What’s the next thing you ask when the boy you’re pretty sure you’re in love with says he’s a faerie? A thought occurs to me. I think of my historic books, of my aunts and my father, scattered throughout Boston’s chronology. “So is…everyone a faerie?”

“That’s a complicated question,” Ben says awkwardly.

“How did I get involved with all this?” I’m not even sure I expect an answer to the question. I am asking it mostly of myself, but Ben answers.

“You were born involved.” Ben resumes walking.

I follow, asking again, “Where are we?”

It’s the rat who answers me. “It’s his home.”

“How did we get here?”

“He’s a traveler.” The rat actually sounds proud of this.

There’s that word again. I look at Ben, and there is a trace of a smile on his face.

“What does that mean?” I ask.

“I can jump,” Ben explains, “from place to place. Although it’s harder for me when I’m wet, which is why we ended up here instead of Boston. Easier for me to lock on to the Otherworld than the Thisworld.”

“And that’s something faeries do? Jump?”

“No. Just me. It’s something travelers do.”

“You can’t keep her here,” the rat interrupts us.

“I know that. I told you: we’re going to Parsymeon.”

“I thought we were going to Boston,” I say.

“Her mother is looking everywhere for her,” says the rat.

I stop walking abruptly, rounding on him. “My mother?”

The rat ignores me. “She sent the Green Line after you; you barely made it here. How do you expect to hide the fay? You’ll never be able to. The Seelie Court will arrive with a chiming of bells—”

Ben stops walking abruptly, turns, and picks up the rat by the scruff of its neck. It squirms in his grip and demands, a ratty squeak finally emerging in its voice, “Put me down! Put me down this instant, boy!”

“You insist on personifying yourself as a rat, then I will insist on treating you like one,” Ben snaps. “And you’re not helping. Stop. It.” He punctuates the words with a little shake.

“You can’t run from the entire Seelie Court. How will you do it?”

“Stop it,” I shout. “Stop talking.”

Ben looks at me. The rat, still dangling from Ben’s hand, looks at me as well.

“What is he talking about?” I demand. “My mother is looking for me?”

Ben looks at a loss, which is really a terrifying thing to see.

I feel cold. “How long have you known this?”

Ben says nothing, which is incriminating.

I stumble away from him. Suddenly I can’t bear to be near him. “I’ve been trying to find her. You never said…anythi

ng—”

“Listen to me.” Ben drops his father and makes a grab for me, but I dodge him. “You can’t have her find you.”

“Why not?” I demand.

“I’ll tell you everything—everything, I promise, but not here. We have to get to Parsymeon.”

“No.” I shake my head. “I don’t know what that is. You said we were going to Boston.”

“That was before the Green Line train came. Parsymeon would be safest. It’s a form of Boston; it’s pre-Boston—”

“I don’t care. Take me to Boston. Take me to my aunts.”

The rat looks at Ben. “Well,” he remarks, “you’re in trouble, aren’t you? The fay has spoken.”

CHAPTER 6

Ben takes a deep breath. I stand watching him, wary and stony, and terrified and furious.

“Fine,” Ben says. “Boston. Take my hand.”

I don’t.

“I can’t jump you if you’re not touching me.”

“Now, all of a sudden, you can jump us to Boston? You couldn’t before?”

“I’m dry now,” he snaps. “And I’m home. I’m more powerful when I’m at home.”

“Boston,” I say firmly. “My aunts.”

“Yes,” he agrees, sounding irritated.

I take the hand he’s offering, and there’s a moment when I’m looking straight into his unusual eyes, all blue and green in this land of meadow and sky, and then I blink and we are standing in Park Street again. It is Park Street, and people are dodging around us, everyday Boston people going about their lives, and Ben’s eyes are a flat, slate gray in the damp and gloomy T station.

“Do be careful,” an attractive man in a black suit snaps at Ben, and Ben dodges away from him, using our joined hands to pull us forward.

“Damn goblins,” he mutters.

I try to turn my head to look back, saying, “That was a goblin?” but the man has already disappeared.

We emerge from the T station into Boston. It looks exactly the same as it always has. How can I possibly believe this crazy story about enchantments and faeries? Then I realize that someone is sitting on our stoop—someone who turns out to be Will from the Salem Which Museum. I stop and blink at him in astonishment. I feel Ben draw to a halt next to me.

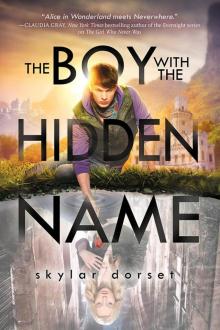

The Boy with the Hidden Name

The Boy with the Hidden Name The Girl Who Never Was

The Girl Who Never Was Girl Who Never Was

Girl Who Never Was Girl Who Read the Stars

Girl Who Read the Stars The Boy with the Hidden Name: Otherworld Book Two

The Boy with the Hidden Name: Otherworld Book Two