- Home

- Skylar Dorset

Girl Who Never Was Page 14

Girl Who Never Was Read online

Page 14

“It doesn’t matter,” says my mother. “It’s in the past.”

“Yes,” he agrees. “That’s right.” The male faerie pushes his plate away and leans back. A pipe appears from somewhere, and he sticks it in his mouth. Smoke drifts out of it, glowing hazy silver in the darkness around his head. I can’t help but blink at it in surprise. It shouldn’t surprise me—I’m in a faerie prison, after all—but still.

“What are you smoking?” I hear myself ask, and I didn’t even mean to ask it, but I can’t resist, because that smoke is beautiful and dazzling and fascinating.

“Stardust,” he answers me. “What else?”

CHAPTER 19

I am sitting by my glassless window when my mother arrives the following morning. At least, it seems as if it’s morning—I watched the sun rise—but time seems to move oddly here. It should be morning, surely enough time has passed for it to be morning, but at the same time, I feel like it’s only been a few minutes since my mother left me in my room, a cool kiss on my cheek that wasn’t the least bit comforting. I haven’t slept. I miss my aunts. I wonder what I’m doing here, why I wanted so desperately to meet this mother I have who is so distant and terrifying. I was so stupid to be asking questions about her. Such an idiot. I wish I could talk to Ben. I would feel better if I could talk to Ben. Ben always makes me feel better. I wonder if it’s as simple as asking my mother if I can. I guess it’s worth a try.

“Can I see Ben?” I ask.

“Who is Ben?” she asks and then realizes, “Oh, Benedict? Clever of him, of course, not to give you his real full name.” Her eyebrows flicker upward, as if she is surprised. “But I thought you’d have forgotten him by now,” she says vaguely. “But, of course. If you wish.”

She leads the way. I follow slowly. I am tired of feeling lost. What can she do to me? She cannot force me to go faster.

She keeps rounding back, impatient and complaining, but I persist in my steady pace, memorizing the path. I want to know how to find Ben on my own.

We arrive, finally, at Ben’s cell. He is lounging on his back again, frowning up at the ceiling. I want to ask him what he’s thinking so hard about, but it doesn’t seem like the right thing to say right now. Maybe later. Maybe when I get Ben out of here, I’ll ask him what he was thinking so hard about this whole time. This will be after I shout at him for getting himself into this predicament in the first place. And possibly after I kiss him too.

“Good morning, Benedict,” sing-songs my mother, and the flinch is far more evident this time. “Selkie wished to come see you, didn’t you, dear?”

The pinch from her saying my name is almost familiar now.

Ben turns his head to look at me briefly, his expression inscrutable, and then looks back toward the ceiling.

“Well, Selkie?” continues my mother. The pinch is more severe the second time, like I am already more sensitive. I wonder how Ben has been standing this. “Did you have anything in particular you wished to discuss with him?”

I have a million things I wish to discuss with him. I want to tell him I’m so hopelessly confused that I don’t know what to do. I want to say that I feel like I don’t know who I am anymore. I want to tell him how badly I want to go back to my birthday, when we sat on the Common on a golden autumn day and I loved him so much it hurt, thought he might love me back. But I don’t want to say this in front of my mother. Honestly, I’m not sure I want to say it out loud in front of anyone at all, including Ben. It’s almost embarrassing enough to be thinking it just to myself.

“Hi,” is what I manage, and even though it’s just one word, I feel, when Ben looks at me with his moonbeam/sunbeam eyes, that he can hear everything I’m thinking in it.

Ben opens his mouth then closes it. There is an expression in his eyes, almost a faltering. He finally says, “Hi. Pretty morning, isn’t it?”

It is, actually. There is a single window, high in his cell, and the sunlight coming through it is so bright it feels almost pink.

My mother is looking curiously between us. Then she reaches out casually, trailing a finger in the rapids of the moat before splashing Ben. Ben gasps, sitting up and moving as far away from her as he can get without being splashed by the spray of the moat on the far side of the circle, drawing his knees up to make himself less of a target.

I flinch in solidarity with him and say, before I can help it, “Stop. He doesn’t like water; he doesn’t like being wet.”

“Obviously,” agrees my mother. “None of the Le Fays ever could bear to be wet. Isn’t that right? Benedict Le Fay?”

Ben squeezes his eyes shut, and I can almost see him rocking with the wave of his name coupled with the splash he just received. My mother looks at me and says his name again. I watch him rest his forehead against his knees and breathe quickly, sucking in rapid breaths.

“Stop it,” I say. “Can’t you stop it?”

My mother looks at me evenly. “Interesting,” she says. “Don’t you find that interesting, Benedict Le Fay?”

Ben winces with pain.

“Obviously I could stop it,” my mother says flatly.

Ben hisses, and I look from my mother to him. A thin, fine, persistent drizzle has materialized over Ben. He may still have layers on, but he is still going to be soaked eventually.

“Time for breakfast,” my mother says to me.

I pause, at a loss, as she walks out of the cell. I look at Ben, whose teeth are chattering.

“I don’t know what to do,” I blurt out.

“Just keep breathing,” Ben says, as if that’s helpful.

I wish I could shake him in frustration.

“Selkie!” my mother calls to me, a pinch in the name.

I toss Ben the roll I saved from dinner the night before, which he catches reflexively, looking surprised.

“That’s not really very useful advice,” I inform him quickly, keeping my voice down.

“Better you keep breathing than stop breathing,” he replies.

Words to live by, I suppose dryly, as my mother calls me again.

“Go,” says Ben solemnly. “Best way to keep breathing.”

“I’ll be back,” I promise him.

“Just keep breathing,” Ben repeats.

CHAPTER 20

After breakfast, I am sitting in the overly bright garden room, my thoughts going around in circles, when Gussie suddenly appears next to me.

“Well now,” she says and sits next to me with a smile. “So good to have someone else here to talk to.”

I look at her, and I wonder what her deal is. She seems friendly enough, but I don’t know if I should trust anyone. Never trust a faerie, I have been told, and I am surrounded by them now.

She seems to read my suspicious mind. “They would tell you I’m a guest. Which I suppose is true because, like you, I can wander around here a bit. Unlike Benedict.”

Ben’s name has me sitting up and blinking. “What do you know about Ben?”

“That he doesn’t like water,” Gussie says simply, as if that’s anything at all that I care about right now. Gussie is looking pointedly at the Seelies drifting all around us. “We can’t talk right now.”

This is frustrating. We’re in a Seelie prison. Where are we ever going to be able to talk? “Then when can we talk?” I demand.

“I’ve been here longer than you have,” she says cryptically. “I know my way around here.”

“This place is a maze.”

“Not if you look at it the right way.”

This woman talks entirely in riddles, and I find it incredibly annoying. I wish she didn’t seem like my only chance to get Ben and me out of here.

I look around at the Seelies and notice for the first time other faeries in among the Seelies, flickering through them. They are insubstantial, almost like ghost faeries, like I can only see them out of t

he corner of my eye, not head on. They could almost be a trick of the eye, a hallucination. I feel like I could be losing my mind, but it always seems to turn out that everything that makes me feel like I’m insane is actually true.

I try to tilt my head just so to catch glimpses of their unsteady outlines. If I look too closely, they seem to just dissolve into dust motes. But it doesn’t matter that I feel like I can only sense seeing them, because now that I’ve become aware of them, I can feel them. There is something achingly melancholic and sorrowful about them, and I want to somehow break through to where they are and yank them back into fullness.

Gussie seems to know what I’m doing. “Ah,” she says. “You’ve spotted them, have you?”

“What are they?” I cannot make the question louder than a breath.

“Named faeries,” Gussie says. “That’s what happens when a faerie is named. They dissolve like that.”

“Are they…” I can’t think of how to formulate the thought I want to say next. “Where are they?”

“They’re here. With us. Just dissolved so that they can’t get through. I’ve always thought they must feel dreadfully lonely.”

I can’t help but ask, “Why?”

“Because,” she answers. “Can’t you hear them crying?”

And now that she says it, I feel like I can, a long, low murmur of heartbroken sobbing. I blink in surprise. “Why didn’t I hear that before?”

“Do you think the Seelies want to hear that all the time? They buffer it, naturally.”

“Then why can I hear it now?” Even as I say it, the sound vanishes.

“Because I dropped the barrier for us,” says Gussie.

I look over at her, and I want to ask who she is exactly.

Then my mother suddenly appears with an armful of yarn. She looks at Gussie with narrow eyes and says, “Time for you to be leaving, isn’t it, Lady Gregory?”

Gussie inclines her head with a cool smile and rises. She gives me a look just before she leaves, but I have no idea what the look is supposed to mean. I wish people would stop assuming that I know what I’m doing.

My mother sits next to me and says gaily, “Don’t you think it’s time we got to know each other better?”

I blink at her. “Why?”

She is fluffing at the pile of yarn on her lap. “Oh, you know.” She looks at me, those unnerving colorless eyes directly on me. “We are fellow Seelies.”

What we actually are is mother and daughter, but she doesn’t seem to care about that.

“I am not entirely Seelie,” I remind her.

“Oh, yes, you are,” she says confidently and turns her attention to the yarn on her lap, winding it randomly around her fingers. I have no idea what she’s doing with it. “The longer you stay here, the more that will be true. All memory of ugly things will fade for you. That’s the charm of the Seelie Court. We don’t allow ugly things to exist here. Ugliness is ferreted out and destroyed. So it will be with you, inside of you.”

I feel cold. “What do you mean? I’ll just…forget?” That was what Will warned me of, after all, that they would try to make me forget who I am.

“Eventually. But it will be better that way. It was better when I’d forgotten you. Then Benedict Le Fay’s enchantment broke, and we all remembered you are that damnable prophecy, and it was pleasanter before.”

“You forgot about me?” I am horrified by this.

My mother continues twirling her yarn. “Of course. Why wouldn’t I? So unpleasant. Why would I wish to remember? Memories are terrible things, my dear. We would all do better to be rid of them. Mortals don’t realize this. People like Will Blaxton, constantly scribbling words in books. Histories. Do you know the dangerous power of words on paper, freezing the memories, making them there, fixed points, keeping track of time? One should never try to keep track of time. It is so dangerous, so insidious. Keeping track of it is not the way time works. You were born a century ago—or was it weeks ago? See? So difficult to tell, and so much better that way.”

I think of my aunts, talking of flighty faeries. I think of how desperately all of Boston clings to its sense of history, how you can’t walk two steps without hitting a plaque or a tablet or a statue or a marker or something, words freezing the history into place. Was that Will’s doing? All the supernatural creatures of Boston, violently reacting against the Seelies’ campaign to eliminate history, memory, time? I think of Beacon Hill, frozen in time, standing strong against those who would tear it down, make it new, forget it. My hand closes around the battered pages of history in my sweatshirt pocket. Words and pictures, my aunts and father—how could I forget them?

“There’s a prophecy about you,” my mother continues. “I’m sure you’ve been told. But not one prophecy. No one ever has one prophecy. A web of prophecies. This is the one where you claim your blood right, stay a Seelie. You will lead us to the other three fays of the seasons, and our reign will be cemented forever. That is what the prophecy says: that we will never fall, ever, as long as the fay of the autumnal equinox remains here with us.” My mother’s eyes shine as she says this.

I stare at her, because this is not like any prophecy I have heard. Did everyone else have it wrong, thinking that I would overthrow the Seelie Court? When my mother thinks that I will help it reign forever? What does “a web of prophecies” even mean? What is the point of a prophecy if there are other prophecies competing against it? I am so endlessly confused.

So I ask the only thing I can think to ask. “And what about Ben?”

“Oh, we can name him if you like,” she says negligently, frowning at the yarn on her lap, still twirling it this way and that. It still just looks like a random pile of yarn to me. “I’ve only refrained as a gesture of good will.” She glances up at me with one of her anti-smiles. “My dear.”

“I don’t want him rained on. I don’t want him wet. I don’t want him imprisoned.”

“Oh, well, that must be so. He is far too talented, and his memory is too long. Benedict does not have a cooperative nature. It is a failing that afflicts all the faeries in his line. Unfortunate, really. You’ll see. You’ll come around.” My mother twists at her yarn and I sit, freezing in the bright, angry sunlight.

***

That night, after my mother leaves me in my room, I count carefully to one thousand and open my door.

I move through the dark hallways, using the route I’d memorized that morning and repeated to myself all day. I am not entirely sure it will work, that it won’t be enchanted away from me, but then I have reached Ben’s cell. I wonder if I was successful in memorizing the route or if this is Ben’s enchantment: I didn’t want to lose my way, so I didn’t. Could it be that easy?

The moat is still rushing around Ben, and the rain is still falling over him. Moonlight is slanting through the window, and I can see from its glow that he is curled into a ball, back to me, huddled into his layers as much as he can be.

I clutch the blanket I’ve brought for him and take a running leap over the moat, just making it. It may be a deep moat, but thankfully it isn’t an especially wide one.

“Ben,” I hiss at him, spreading the blanket over him quickly. I crouch in front of him. His collars are pulled up over his face as much as they can be, and he is completely unresponsive.

I take a deep breath and lay on my side facing him, reaching for his hand under the blanket and sliding my hand into it. Please let this work, I think desperately, watching him.

It is not instantaneous, the way it was on his home world, what seems like oh-so-long ago—literally a separate lifetime ago. But I wait, patient, counting in my head, wondering how high I will count before I give up, and then, finally, he stirs. I want to weep with relief. When his eyes flutter open and focus on me, I think it is eminently possible that I am going to.

“Selkie,” he says blurrily, closing his eyes again

.

“Say my name again,” I tell him. “Will said it would help.”

“Selkie,” he says, more clearly this time. “Selkie Stewart.”

“There you go,” I praise him with false gaiety.

He is shivering violently now. “I’m so wet,” he says, teeth chattering. “I’m so, so wet.”

“I know.” I sit up, wringing rain out of his hair. “What can I do, Ben? Tell me what to do.” I am so tired of feeling helpless, but I feel desperately out of my depth. I wish I’d thought to bring an umbrella.

He pulls at me feebly. “Dry,” he says. “You’re dry.” He slurs the sentence together.

I’m not really dry, but I suppose, to him, I feel like a day in the desert. I get the gist of what he is trying to do, cuddling close to him, and he buries his face against my neck, leaving me covered with rain, but hopefully leaving himself drier. He is still shivering in my arms, but he does sigh with relief. “Say my name again,” I tell him, pulling the blanket up over both our heads.

“Selkie Stewart,” he says against my skin. “Selkie Stewart, Selkie Stewart, Selkie Stewart.” He is shivering less now, and he is holding me more tightly, and that is a relief, that he is no longer limp. “Oh, Selkie Stewart,” he says. “It was so silly of you to come.”

“I’m so sorry,” I choke out. “I didn’t mean to make it worse.”

“You haven’t made it worse. It’s almost exactly the same. Except now you come and bring me blankets. Selkie Stewart. I’m so happy to see you.”

It is absurd, because we have never been in more dire straits, but those words warm me all the way down to my toes. I close my eyes and think how I love him, how I must get him out of here, keep him safe, the way he kept me safe for however long it was in this world without time. “Likewise,” I manage to tell him, combing his damp hair away from my mouth.

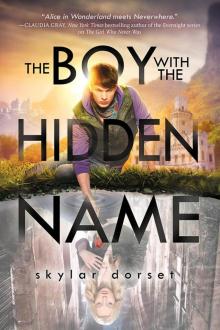

The Boy with the Hidden Name

The Boy with the Hidden Name The Girl Who Never Was

The Girl Who Never Was Girl Who Never Was

Girl Who Never Was Girl Who Read the Stars

Girl Who Read the Stars The Boy with the Hidden Name: Otherworld Book Two

The Boy with the Hidden Name: Otherworld Book Two