- Home

- Skylar Dorset

Girl Who Never Was Page 11

Girl Who Never Was Read online

Page 11

CHAPTER 15

The woman immediately moves past me, confidently striding in the direction of the conservatory. Still clutching her basket of sewing supplies, I hurry after her, eager not to miss anything.

She takes my seat, which is the only one not covered with bats, and gestures for her basket. I hand it over and then stand and look about me for somewhere to sit that has not already been monopolized by the bevy of bats. Kelsey moves a tiny amount, disturbing a bat who turns a glare on her, but it is enough for me to squeeze in next to her.

“Now then,” says the woman calmly. “Who is the honor-bound faerie?” She is carefully threading a needle as she speaks.

I look at my aunts, who aren’t looking at me. Aunt True is worrying at a nail and looking at the floor. Aunt Virtue is watching the bats lined up on our mantelpiece. I look at Will, who is frowning magnificently at the woman who has entered. Nobody seems to be giving me any guidance, and I have no idea what to do.

The woman stops threading her needle and looks up expectantly. Her dark eyes scan the room and land on me. It is as if she did not see me at all when I opened the door for her. She stares at me, transfixed. She replaces the needle and thread slowly into her basket and then breathes, “Oh.” Extending a hand toward me, she then commands, “Come here, child.”

My aunts still aren’t looking at me, so I look at Will, uncertain. There is one thing I am sure of—in the hierarchy of people from the Otherworld I trust, Will ranks above this strange woman.

Will nods at me, although he still looks grim, and not knowing what else to do, I stand up and walk slowly over to her.

“Oh my,” she exclaims, taking my hand in hers and squeezing gently. “I had been wondering how an honor-bound faerie had gotten into Boston. It’s been ages since my services were needed. So you’re what all the fuss has been about. You’re the fay of the autumnal equinox. Aren’t you lovely? But where is Benedict Le Fay? Sulking now that his enchantment has been broken? How came you to break his enchantment, child?” she asks me kindly and curiously.

“His name,” I answer truthfully.

“Do you know Benedict Le Fay’s full name?” she asks sharply.

I suspect that, if I did, there is nothing this woman would stop at to extract it from me. But I am able to truthfully answer, “No.”

“You broke his enchantment with how many of his names?”

“Just the two,” I respond, confused. “Well, three, I guess, depending on what, exactly, Le is.”

“Two names,” she muses. “You broke a Le Fay enchantment with just two names. That is some clever naming. That talent must be strong with you.” She takes a deep breath and lets it out again. “Now. What have you gone and gotten yourself honor-bound about?”

I hesitate, unsure.

“Well, go on,” the Threader urges. “You called me here.”

“I didn’t,” I say uncertainly.

“Yes. You did. An honor-bound faerie. I am here to weave your obligation into the tapestry, to record it forever. Or at least the next few minutes, depending on the time you’re keeping.”

I stare at her. “What tapestry?” I ask, still uncertain.

She stares back at me, as if we are in identical stages of shock over the other. “The tapestry,” she insists, which isn’t exactly helpful.

I look at my aunts for guidance. Something about this woman, this unknown tapestry, this obligation talk makes me uncomfortable.

“But she isn’t actually a faerie,” Aunt Virtue interjects pleadingly. “Surely that means—”

“But she is a faerie. I wouldn’t have been called here if she was not.”

“She is only half-faerie,” Aunt True adds desperately.

“Nevertheless, it is a full obligation.” The Threader acts as if the conversation is now closed, and my aunts, looking dejected, don’t fight anymore, so maybe it is closed. She looks at me expectantly.

I swallow.

Will says, “Oh, you might as well get it over with. You’re the one who was so set on going in the first place.”

I lick my lips. This is apparently my cue to plead my case. “Ben’s in the faerie prison, whatever it’s called. And he’s there because of me. It’s my fault. So I have to go save him.”

The woman’s eyebrows flicker upward. “Tir na nOg?” she asks. “Are you talking about Tir na nOg?”

“Yes,” I say, recognizing the strange phrase.

The woman continues to look dubious. “You’ve gone and gotten yourself honor-bound over saving someone from Tir na nOg?”

“I can get in,” I say stubbornly. “They want me there. They’ll let me in. They’ll probably have a welcoming committee waiting for me.”

“Oh, they’ll have a committee,” mutters Will dryly. “The adjective used to describe it might not be ‘welcoming.’”

“There will be no trouble getting in, child. They will send a Green Line train for you, of course. The trouble will be getting out.”

“A Green Line train?” I echo. “Like the subway?”

“Yes.”

I am thinking hard. So I just have to get on the Green Line and it will take me to the faerie prison. This seems unlikely, but everything that’s happened to me recently seems unlikely, and who am I to argue with the idea that there’s a faerie prison at the end of the Green Line? The Green Line is strange.

“The problem is once you’re there,” says Will. “No one’s ever escaped Tir na nOg.”

“Except for Benedict Le Fay’s mother,” remarks the Threader.

“Ben’s mother?” I say sharply.

“Oh, that’s a literal faerie tale,” says Will. “There was never any evidence that she escaped; she hasn’t been seen since. The only people who get out of Tir na nOg are mad.”

“Mad?” I echo.

“They’re insane, Selkie. Did you never wonder what drove your father to insanity? That’s what contact with a Seelie can do, even without being imprisoned by them. That is the price they can exact. They steal who you are, what makes you you. Think of how much worse it is in their court.”

I stare at Will, and I think of my father. It is one thing for my mother to apparently want to kill me. It is another thing for my mother to be holding Ben hostage in some kind of unpleasant circumstance in order to entrap me. But somehow, it is more than I can bear to think of her driving my poor father into madness, a man whose dearest wish was a child, a man I have never had an unsupervised visit with because of her.

“I’m a Seelie,” I point out, and I try to sound firm about it, but I can hear the tremble in my voice. “I don’t drive people mad.”

“You’re only half-Seelie,” Will counters dryly. “It’s the ogre in you that they’ll drive mad.”

“This is all pointless,” inserts the Threader suddenly. “They’ll name her as soon as they see her.”

“And I’ll die,” I finish and try to wrap my mind around that. I feel very detached from it somehow. Maybe this is the only way you can face the looming circumstance of your death, by detaching from it so that it feels like it would happen to someone else.

“Faeries don’t really die,” the Threader corrects me. “They drift. They drift into dandelions and bumblebees, into the ringing of distant bells you can’t pinpoint, into the sparkle of the sun on the sea. They drift until there is nothing left of them.”

She says all of this matter-of-factly, but it sends a terrible shiver of foreboding down my spine.

“As they drift, they are mad,” inserts Aunt Virtue, staring off into the distance, caught up in a recollection. “It is a terrible, awful thing to see.”

“I saw one once,” adds Aunt True, her voice no louder than a whisper. “Before we came here. I will never forget it.” Looking horrified, she shudders.

“They won’t name me,” I promise them with a confidence I don’t feel. Wh

y wouldn’t they name me? Why wouldn’t they name me before I could get anywhere near Ben? For a moment, I think that Will is right and this is the foolhardiest thing I could ever do. And then the next moment, I think of Ben, of the quickness of his smile, of the light in his pale eyes whenever he looked at me. I think of Ben, covering me in a sweatshirt of protection and sending me away and begging me to remember him. I think of Ben, scared and alone in some terrible prison because he wanted to keep me safe. I look at my aunts and take a deep breath and say again, “They won’t name me.”

My aunts look at me with dark eyes wide with sadness.

“Wait a moment though,” says the Threader thoughtfully. “I understand that you feel you are honor bound, but your life is not entirely your own, is it?”

I look at her sharply. “Yes,” I retort. “Of course it is. Who else’s would it be?”

“Well, it’s ours,” she answers simply. “All of ours. You are the fay of the autumnal equinox. There’s a prophecy about you. You have a duty to fulfill the prophecy.”

“But it’s my prophecy. The things I do—like save Ben—will fulfill the prophecy.”

The Threader gives me a coolly mocking look. “You really think prophecies are so simple? So straightforward? Do you know how many strands of thread weave in and out of each other over the Thisworld and the Otherworld? More than any mere faerie could count. All of the threads of all of the beings and all of the threads of all of the choices they make and fail to make, and you must follow those threads, must see them woven together in exactly the right way for any prophecy to come to pass. Prophecies are merely one way of reading the stars. Do you think that a prophecy as important as this one truly depends on the headstrong, stubborn decisions of some small slip of a girl?”

I look at her for one silent moment, and then I answer, simply, “Yes.”

“You will not go to Tir na nOg,” says the Threader sharply.

“I thought you were supposed to be weaving my obligations into your tapestry,” I point out hotly. “This is my obligation.”

“I weave the obligations of faeries that have nothing to do with me. But do you think I am compelled to do so? Do you really think I exercise no control over how the tapestry is woven? Do you truly believe that I have no power? I, who have survived this long? How dare you?” She draws herself up. “I am the Threader. If I say you will not do something, you will not.”

“How could you stop me?” I demand recklessly.

“With my thread, of course,” she replies, and then she does something I don’t expect. She catches up a threaded needle in her hand and lunges at me with it. I think her intention was to prick the skin on the back of my hand. I don’t want her to touch me, I think. The needle gets within a hairsbreadth of me and will go no farther.

Absolute silence falls over the room. I had flinched at the Threader’s movement, but now I stand very still, staring at the needle poised over my skin. The Threader is also staring at it. Everyone is. The Threader withdraws her hand and tries again, plunging the needle toward my skin. Again, it stops a hairsbreadth away from me, and I can see the Threader’s fingers around the needle quivering with the effort of trying to pierce through Ben’s enchantment.

The Threader snaps. She flings the needle across the room, the thread unraveling out of it, clearly in a towering temper. She screams to the sky in frustration, and the scream rises and rises in pitch, and the bats around her take flight, flapping wildly around the room. The very walls around us seem to tremble. Everything is chaos, and in the middle of the whole thing, I know I have to make a break for it. Through the flurry of the bats, I dart over to my aunts and kiss each of their cheeks.

“But—” says Aunt True feebly.

“Be back before you know it,” I promise breathlessly, and then, for reasons I can’t explain, I stoop and pick up the threaded needle and pocket it before dashing out of the room. Things in the kangaroo pocket of my sweatshirt seem to be important when you least expect them to be, and I don’t have time to stop for any other supplies.

The Threader is still shrieking her displeasure. “Come back here! Come back here immediately!”

I duck through the swirl of bats, battering them away from my face, and tug open the door. She can’t make me go back, I think. Ben’s enchantment is coming in handy after all.

“Selkie!” I hear Kelsey call, and I hesitate on the doorstep, guilty, and then shout back to her, “I have to go!” before darting across Beacon Street and onto the Common. I weave around the tourists and get to the subway station. It is still in chaos from the fire on the tracks, annoyed commuters complaining loudly to the world at large about the incompetence of the subway system. I get to the turnstile and swipe my card through, and everyone around me disappears.

The silence is terrifying. I look around the suddenly empty subway station and try not to panic. All of this stillness is far more panic-inducing than the teeming crowds had been. I am used to the press of people—the subway station is in its natural element then. Here, now, I feel completely lost. And for the first time since I got it into my head to rescue Ben, I suddenly fully comprehend why nobody wanted me to do this: because I have no idea what I’m doing and will probably get myself killed.

I take a deep breath. I can’t turn back now. Ben is depending on me. I swallow and am just about to push through the turnstile when the door to the subway station opens.

I whirl, startled now at the idea that someone else is here with me. And it’s Kelsey. “Bats,” she announces dramatically. “I had bats in my hair.”

“What are you doing here?” I ask her.

She is looking at the eerily empty subway station. “Where is everyone?”

“You’re not supposed to be here,” I tell her.

“Well, I’m here. Your aunts are so devastated that they’re sobbing, and the wizard and the sewing lady are busy arguing about some love affair they had a few centuries ago, and do you realize that I think we’ve both hit our heads and are having some kind of shared hallucination?”

I look at Kelsey, such an anchor of normality in the craziness that has been my life, and she has been for as long as I’ve known her. I feel like crying suddenly. Just the other day, we were in class complaining about the impossibility of pre-calculus, and now I’m going to save my faerie quasi-boyfriend from a faerie prison where he’s been put by my mother, who also wants to kill me. “I’m in love with him,” I say, because it’s the first thing I can think of to say, because I feel like it might explain everything, because I’ve never admitted it out loud before. “He’s some kind of weird enchanting faerie, and I have no idea if I can trust him, but it doesn’t matter because I’m in love with him.”

“You’ve never even mentioned him,” Kelsey points out, which is fair.

“I know. I’d forgotten him. And then when I knew him, I… My life is a mess.” I give up trying to explain it.

“So I gathered.”

A train squeals ominously into the station. A Green Line train. I look at it and say, “That’s for me.”

“I’ll go with you,” Kelsey says immediately.

“You can’t,” I tell her. “You can’t. This is all so crazy, and I’m already being selfish and breaking my aunts’ hearts, and I never even said good-bye to my father, and I can’t be the reason anything happens to you. I can’t. Please, Kelsey.”

Kelsey looks at me for a long moment and then pulls me into a fierce hug. “Don’t cry,” she commands, even though she sounds on the verge of it herself. “This is a stupid thing to cry about. I’ll see you in school tomorrow, and then afterward you’ll introduce me to this boyfriend you’ve been keeping a secret.”

“We’ll be recovered from our shared hallucination in time for school tomorrow?” I ask, a weak joke.

“Yes,” Kelsey says and hugs me a bit tighter. “Absolutely.”

I cling a little bit to Kels

ey, trying to freeze-frame the feeling of being here with someone who likes me and loves me and wishes me no harm and only good things. I have a feeling I’m going to need to remember what that’s like.

Then I turn and take a deep breath and push through the turnstile and walk up to the train, whose doors slide open with a chiming of bells.

I am just about to get on the train, just about to put my foot on the first step, when the subway station door bangs open. I look back, and Kelsey looks up the stairs behind her in surprise, and then Will comes jogging down the stairs.

“Wait,” he commands me and pushes through the turnstile. “Wait, wait, wait.”

I set my jaw. “I’m going,” I tell him.

“Fine. Yes. I can see that. Anyway, they’ve sent a train for you, so you’ll never outrun it at this point.”

“Ben outran a Green Line train.”

“He’s the best traveler in the Otherworld; he can do that. If you’re determined to go and do this stupid thing, then there’s something you need to know. You are…extraordinarily good at naming.”

I stare at him. “What does that mean?”

“You broke Benedict’s enchantment with just two of his names. Snapped it in two. That takes power, Selkie. That takes an extraordinary amount of power, to do something like that to a Le Fay enchantment with only two of his names. There is power in your name; it’s thrumming through it. When you get to Benedict, make him use that power. Tell him to stop being noble about it and use it. Make him say your name. It’s your Seelie blood, and it might be your only chance to get out of there, using the Seelie blood against them.”

“I’m only half-Seelie,” I remind Will.

And Will, to my disbelief, actually smiles. “True. And your ogre blood will get you the rest of the way out. You’re absolutely insane, you know, but you also just broke the Threader’s thread for you, completely unthreaded her needle, and I’ve never seen anyone do that before. So maybe you can do this, fay of the autumnal equinox. Maybe this is your prophecy.” Will looks at me, really looks at me, and I feel like he’s trying to read something, like the future is written in my eyes if he could only look closely enough. Maybe it is to Will. “I hope it is,” he says softly, almost to himself. “I really, truly, genuinely do.”

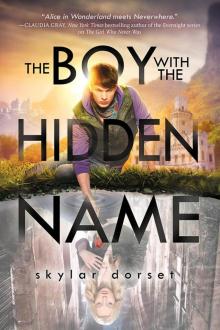

The Boy with the Hidden Name

The Boy with the Hidden Name The Girl Who Never Was

The Girl Who Never Was Girl Who Never Was

Girl Who Never Was Girl Who Read the Stars

Girl Who Read the Stars The Boy with the Hidden Name: Otherworld Book Two

The Boy with the Hidden Name: Otherworld Book Two